The は/が problem isn't you — it's the teaching

You know the rules. Why do you still freeze? 🎯

{{first_name | みんな}}さん、こんにちは ☕

You've read the explanations. Topic marker. Subject marker. You nodded along.

Then you tried to speak — and every sentence became a coin flip.

Here's what's going on: textbooks teach definitions, not decisions.

"は marks the topic" is technically correct. It's also useless when you're mid-conversation, wondering which particle to use right now.

This week, we're giving you something different. Not a flowchart. Not a 47-point grammar breakdown.

One mental model that works 80% of the time — and one exception that covers most of the rest.

Why the explanations don't stick

You've probably encountered explanations like this:

"は is the topic marker. が is the subject marker. They're different."

Okay. But how are they different? When do you use which?

The explanations get fuzzy. They contradict each other. And when you try to apply them mid-sentence, you freeze.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: the problem isn't your understanding. It's the teaching.

Most textbook translations are designed for natural English, not accurate Japanese. And that's where the confusion starts.

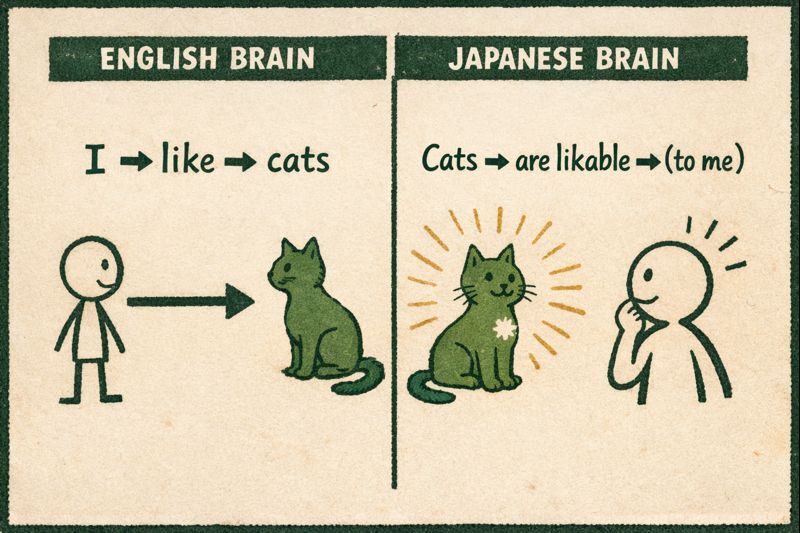

The translation trap

Take this sentence:

猫が好きだ

Well…,

Your textbook says: "I like cats."

That's perfectly natural English. It's also hiding what が actually does — and it's creating a problem you don't even know you have.

Here's what's really happening:

猫が好きだ

= "Cats are likable (to me)"

Wait. Where's the "I"?

There isn't one.

In Japanese, the experiencer — you, the person feeling the emotion — is often implied. It doesn't need to be stated. The sentence isn't fundamentally about what YOU do. It's about what the THING is.

が marks the thing with the quality. In this case, cats possess the quality of being likable. You're not "doing" the liking — you're experiencing it.

When textbooks translate 猫が好きだ as "I like cats," they make は and が look interchangeable. They're not. The translation just hides the difference.

Don't translate first, then add particles. That's working backwards. Instead, ask: "What has the quality? What's causing the state?" That thing gets が.

The worldview shift

This is the unlock that makes は/が finally click.

English says: I like cats. I understand Japanese. I'm scared of ghosts.

Japanese says: Cats are likable. Japanese is understandable. Ghosts are scary.

See the difference? In English, YOU are the subject — doing the liking, understanding, fearing. In Japanese, the THING is the subject — possessing the quality that triggers your experience.

Think about it:

→ You don't decide to like something — it triggers a feeling in you

→ You don't make yourself understand — comprehension happens (or doesn't)

→ You don't choose to be scared — something scary causes that reaction

Japanese grammar reflects this reality. The thing causing the state gets が. Always.

This pattern shows up across emotions, abilities, desires, and perceptions:

In every case, が marks what has the attribute — not you, the person experiencing it.

Once you see this pattern, you can't unsee it. And suddenly, が stops feeling random.

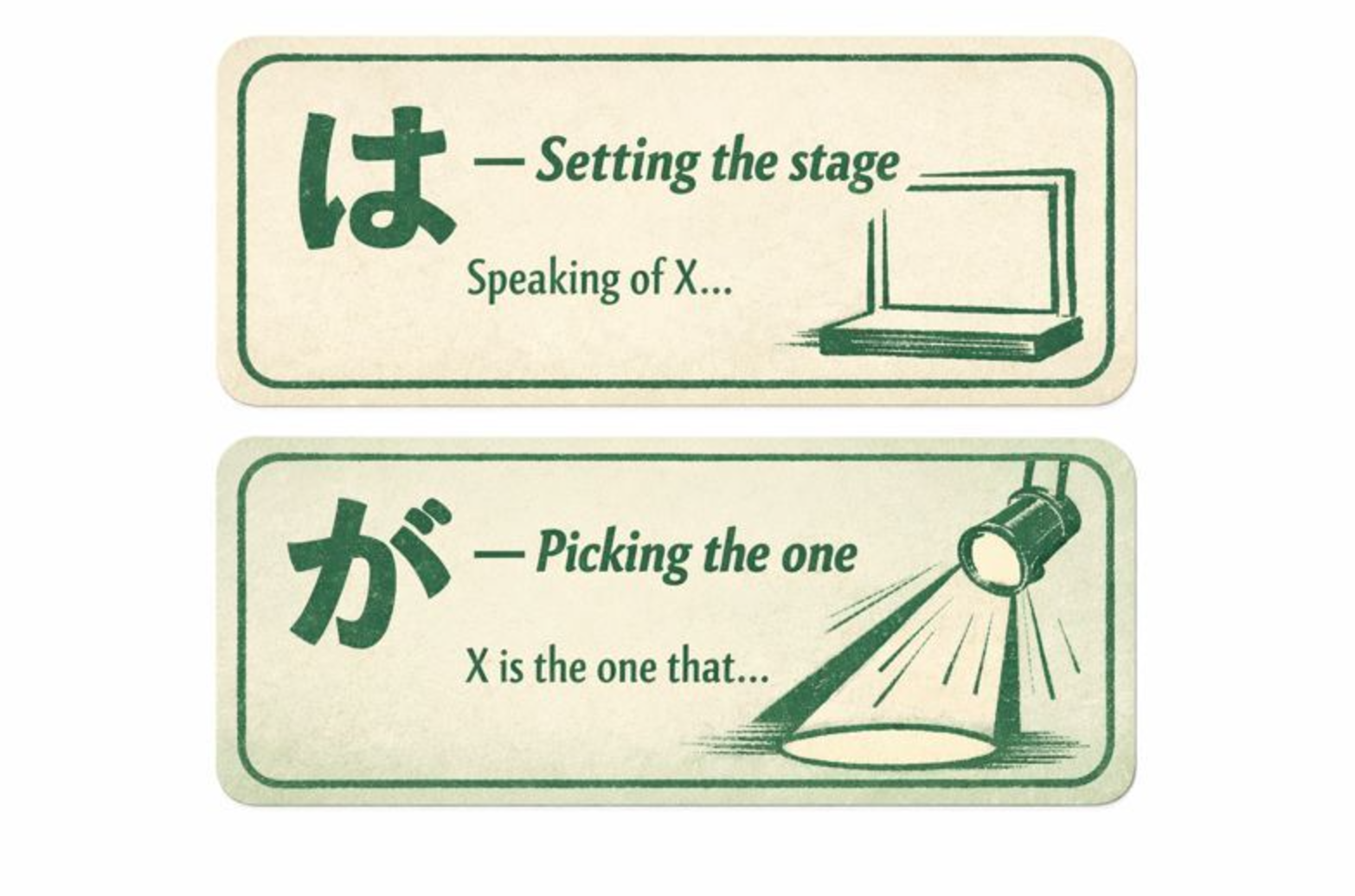

The 80% rule

Now for the practical heuristic you can actually use mid-conversation.

は = "Speaking of X..."

Sets the scene. Establishes what we're talking about. Often implies contrast with other things.

が = "X is the one that..." / "X has the quality..."

Identifies the specific thing. Marks what's doing the action or possessing the attribute.

Here's the anchor pair:

魚は好きです

"As for fish, I like it."

魚が好きです

"Fish is what's likable (to me)."

Same words. Different particle. Different meaning.

With は, you're setting fish as the topic — and possibly contrasting it with other foods. ("Fish? Sure. Shellfish? Not so much.")

With が, you're identifying what possesses the quality of being likable. Fish is THE thing.

One more pair to lock it in:

私は田中です

"I'm Tanaka." (standard intro)

私が田中です

"I'm THE Tanaka." (pointing yourself out)

If someone asks "Which of you is Tanaka?" — that's when 私が田中です makes sense. You're identifying yourself as the specific answer.

The one exception worth knowing

New information gets が.

When someone asks "who?" or "what?" — the answer uses が, because you're identifying something specific from possible options.

Q: 誰が来ましたか?

= "Who came?"

A: 田中さんが来ました

= "Tanaka-san came."

Think of it like pointing at someone in a lineup. が says: "That one. That's the specific thing I'm identifying."

Don't memorize "new info = が" as another rule to apply. Instead, ask yourself: Am I pointing at something specific? If yes, が.

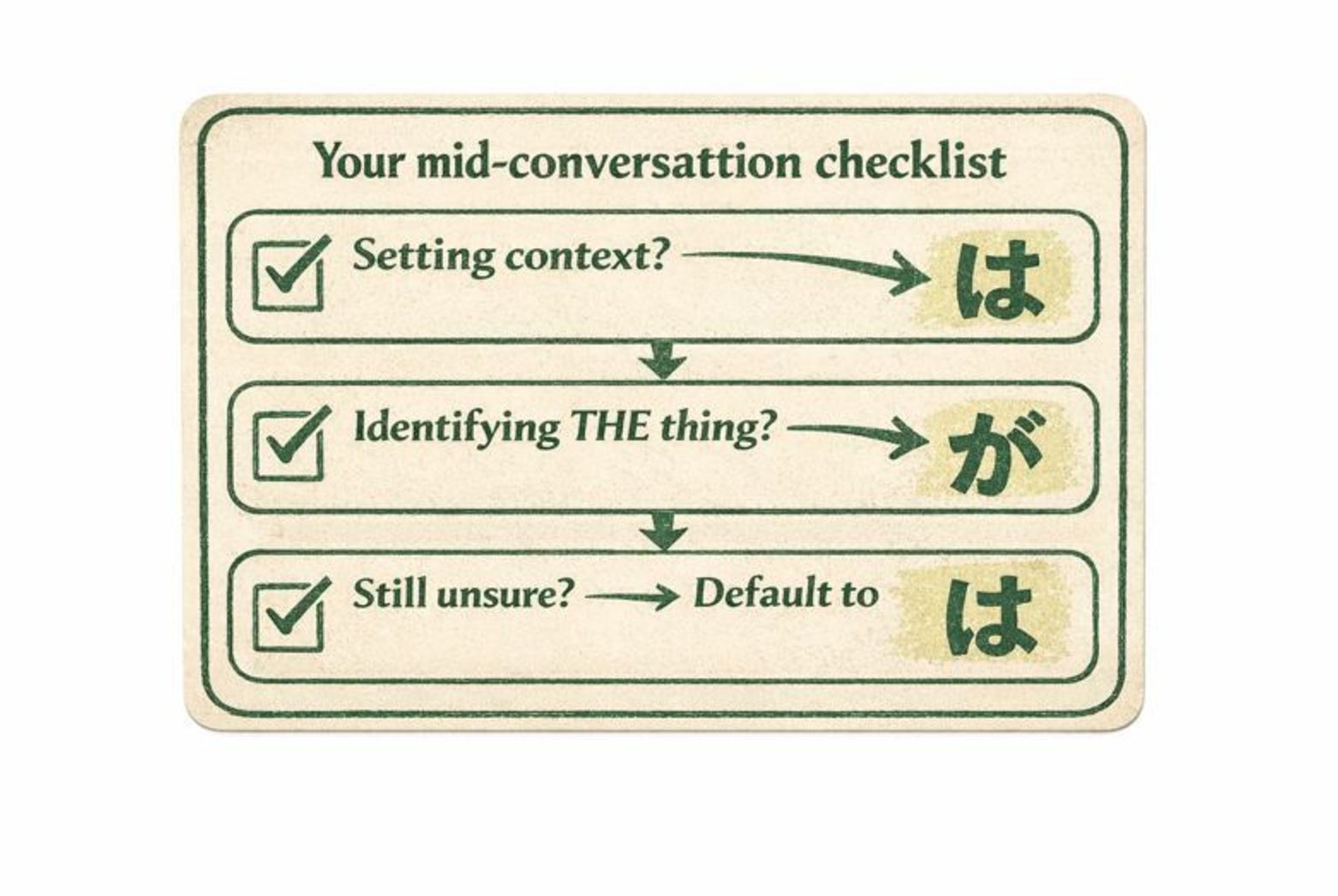

Your mid-conversation checklist

When you're stuck, run this mental check:

1. Am I setting context for what comes next? → は

2. Am I identifying THE specific thing (or what has the quality)? → が

3. Still not sure? → Default to は. You'll be right most of the time.

Natives don't consciously think about this. You won't either — after enough input. The goal right now is survival until the pattern becomes automatic.

Renshuu Time 練習 📝

Find 3 sentences in your current reading or listening that use は or が.

For each one, ask yourself:

→ Is this setting context / establishing a topic? → Probably は

→ Is this identifying something specific / marking what has a quality? → Probably が

Write them down with your guess. No analysis paralysis — just notice and take your best shot.

You'll know you did it when: You have 3 sentences written with your は/が guess for each.

You got 2 out of 3? That's pattern recognition starting to click. Even 1 out of 3 means you're noticing particles now — which is more than most learners ever do.

Level up レベルアップ: Find a sentence where both は AND が appear together. What job is each one doing?

This week's question

Reply and tell us: What's the は/が sentence that finally made it click for you? Or the one that still trips you up?

We read every reply.

これからも一緒に頑張りましょうね〜

— Kotoba Brew Editorial Desk